Why: ClimateSmart.

The risks of investing in oil.

ClimateSmart excludes fossil fuels and its dependent industries because:

Even oil companies are not projecting significant demand growth.

The last big oil innovation lost investors lots of money (fracking).

China has a geopolitical incentive to switch the world to batteries and renewables.

Investment returns are generally driven by industry growth, not stagnation or decline.

Chapter 1: Overview

“Fossil fuels are necessary for investment performance.”

Chances are, even if you personally really dislike the fossil fuel industry, that some part of you holds this belief.

It’s pervasive. We see it all the time. Members will tell us things like: “I’m investing in a ClimateSmart portfolio even if that means lower returns.”

And when we push them on what they mean, it’s not that they expect climate solutions to underperform, or green bonds, or a globally dynamic strategy (the other pillars of our strategy). It’s that they correlate fossil fuels with delivering strong investment returns.

We disagree.

We don’t think fossil fuels or fossil-fuel dependent industries make sense in a long term investment portfolio like a retirement fund.

Here’s the short version:

- Except when oil prices are unusually high, fossil fuel companies are now a low-margin, high-volume business:

- The costs of extraction are rising as the “easy to get” deposits are exhausted.

- There’s no big technological breakthrough coming to help. The last, fracking, allowed access to new deposits, but it’s much more expensive than traditional drilling.

- Case in point, major fossil fuel companies actually lost money most of the past 20 years.

- And this was during a time of general expansion of demand for their products.

- To address low margins, the industry has moved towards consolidation and scale.

- So, should we enter a period of declining fossil fuel demand, as we believe is coming and the IEA projects will occur by the end of the decade, the process of the fossil fuel industry contracting could be messy.

- They don’t have a bunch of small pipelines, refineries, and tankers that can be carefully phased out.

- Instead each piece of the supply chain is big, expensive, debt-ridden, and low-margin.

- Meaning that if demand does start coming down, it’s only a matter of time until we see the weakest links of the supply chain snap and go out of business.

And here is the long version:

Chapter 2: Oil hasn’t been a strong portfolio performer

While investing is fundamentally forward looking, so past performance is no guarantee of future results, it still can be helpful to start by grounding in what’s happened in the past.

So, let’s assume you are a traditional retirement investor. Maybe an IRA or 401(k) that you put in a set amount each month. You’re not trying to time the market. You just are saving like most retirement savers: “set and forget”

For such investors, it’s hard to make an argument that you would have been better off over the past 20 years with the energy sector (oil, coal, refining, distribution) as a part of your US portfolio.

Of the past 20 years, there has only been one time period where the Energy Sector was not a drag on overall performance for the US stock market (seen in green above). Aside from that, the energy sector has generally pulled down the performance of the US Stock Market.

This is similarly clear in looking at the data graphically. Over the past 20 years, total returns of the entire US Stock Market far outpaced the total returns of the energy sector:

So, looking backwards, it feels pretty clear to us that a traditional retirement saver, making those regular biweekly or monthly investments, would likely have done better without fossil fuels and the energy sector in their portfolio.

But what happened 5 years ago? Over that time period, the energy sector did outperform the overall US stock market and did help pull up the overall index. Is that a meaningful counter argument here?

Let’s look at the performance graph over the past 5 years to tell the full story (again, as of April 25, 2025):

To us, this is a graph of three parts:

- Before January, 2022 - both the energy sector and the overall US stock market followed a similar pattern, climbing from the pandemic lows.

- 2022 - US stocks fell but the energy sector climbed significantly.

- 2023 - the Present - both the energy sector and the overall US market re-synced again, both generally climbing until the markets reacted to the Trump tariffs in 2025.

So what happened in 2022?

Russia invaded Ukraine.

And the price of oil went up over 50% as a result. Oil companies went from making modest profits to extreme ones. Exxon’s annual profits almost doubled from 2021 to 2022.

But, as the price of oil has fallen back, so have fossil fuel company’s profits. And the exception began to prove the rule again, with oil regaining its place as an overall drag on performance over the past 3 and 1 year time periods. (This is also clear graphically, looking from Jan 1, 2023 - April 25, 2025, below).

So why is that? Why, despite the fact that the world runs on oil, and that demand has been steadily growing, has the sector’s stock performance generally fallen behind? And what can that tell us about how fossil fuels could perform over, say, the next 20 years?

The answer is multifaceted. But it begins with the fact that for most publicly traded fossil fuel companies just aren’t that profitable.

Chapter 3: Fossil fuel companies just aren’t very profitable.

What if we told you that over the past year (as of this writing) ExxonMobil generated more revenue than Nvidia (one of the hottest recent tech stocks), Tesla (the largest EV company in the US) and Proctor & Gamble (a major provider of household consumer goods)... all put together?

You would naturally think that would lead to Exxon’s stock doing really well, right?

Not really.

Because revenue is one thing. But what the stock market really cares about is profits, i.e. how much a company earns at the end of the year after paying for all of its costs. This is what can actually be given back to shareholders as dividends and/or reinvested into growing the company (and its profits) further.

So even though Exxon made almost 3x the revenue of Nvidia over the last year, it took home less than half the total annual profit that Nvidia made…

This is the big challenge for oil companies (unless maybe those in Saudi Arabia). It costs a lot of money to invest in large equipment to search, extract, and transport fossil fuels from increasingly hard to access areas of the globe. And the more the “easy” wells get exhausted, the more expensive it gets to maintain the same supply.

So unless oil prices are very high, the profit margins of such companies are thin.

The results of such thin profit margins are reflected in the cash flows of large oil companies over the past 20 years. This report from IEEFA has an eye-opening graphic.

For most of the past 20 individual years, the oil majors have lost money, with the only big exception being a price shock caused by an external factor: a war in 2022.

But profits alone are not the whole story of stock valuations. There are plenty of companies with little to no profits today that are very popular, valuable stocks.

Let’s review that table again:

The stock market is like a giant, crowd-sourced future prediction machine built to answer the question: how much more profit do we think the company will be making in 20 years than it is today?

So, while Exxon is making a lot of revenue today, how much more profit does the stock market think it will be making in the future?

The answer: not much.

One of the main ways to judge how optimistic, or bullish, investors are about a company’s future is its price-to-earnings ratio or P/E ratio.

It divides the company’s total market capitalization (aka value) by its latest earnings (aka profits). The higher the number, the steeper investors believe a company’s profit trajectory will be.

Exxon’s margins were pretty similar to Tesla’s. And yet, Tesla's P/E ratio was over 10x higher than Exxon’s. Tesla’s market capitalization of $920 billion is almost double Exxon’s $469 billion, in spite of earning a small fraction of their revenue and profits.

Why?

The difference between Tesla and Exxon is innovation. Or really, innovation potential. Tesla has a clear pathway to innovating its way into giant revenues, profits, and market-share through its EV, self-driving, and autonomous humanoid technologies. While it’s not at all clear whether Tesla will successfully get there, its potential that investors are betting on.

Exxon on the other hand doesn’t really have any major fossil fuel innovation cards to play that could meaningfully change their trajectory, or even set them apart from other oil companies. There is a finite amount of oil, gas, and coal in the world. And most of the easy, cheap stuff has already been dug up and burned (outside of Saudi Arabia).

So, while there is still plenty of more oil out there, the processes of extracting it are increasingly technically difficult, and therefore expensive.

This truth is perfectly exemplified by fossil fuels’ most recent technological innovation: Fracking.

Fracking was a real technological innovation. It allowed for the extraction of fossil fuels from areas that nobody previously thought possible. It set up the US to go from a net importer of fossil fuels to a net exporter.

But it was also really expensive. From that article:

“From 2006 to 2014, fracking companies lost $80 billion; in 2014, with oil at $100 a barrel, a level that seemed to promise a great cash-out, they lost $20 billion.”

So, in spite of gigantic revenue numbers and the centrality of their products to the global economy, it makes sense that fossil fuel companies are valued so much lower than even a pretty vanilla company like Procter and Gamble.

Their forward-looking fate isn’t really in their hands.

Each individual company is facing fierce competition from the others. They do not have a technological pathway to being able to drill the same barrel of oil at, say, half the cost. Nor does any single player have enough market share to unilaterally raise prices to juice profit margins. The industry is in the doldrums, still benefitting from the high volume of demand for its product, but being squeezed by the increasingly high costs of delivering it.

And all of this was during a period when global fossil fuel demand steadily rose from 83.6 million barrels of oil per day in 2005 to 105.5 million barrels in 2025.

So what will happen to fossil fuel stock prices and their already thin profit margins when demand for oil begins to plateau or even… drop?

Chapter 4: Fossil fuel demand may be peaking

This chart made waves when it came out. The IEA (International Energy Agency, a UN research group) in mid-2024 made the bold projection that we would be seeing peak oil production this decade:

They projected that while we would still see rising demand for petrochemical feedstocks (think plastics), that demand for other oil products like petroleum for powering cars and trucks would actually begin to fall by 2027, leading to a net reduction in oil demand by 2030.

And remarkably, this projection was made at a time of general global economic optimism, meaning that the IEA believed this would be the first time in post-industrial revolution history where we would see a decoupling of economic growth and demand for fossil fuels.

On what basis is the IEA making such a bold claim? Here’s their rationale:

“Based on today’s market conditions and policies, global oil demand will level off at around 106 mb/d towards the end of the decade amid the accelerating transition to clean energy technologies. Surging EV sales and continued efficiency improvements of vehicles, and the substitution of oil with renewables or gas in the power sector, will significantly curb oil use in road transport and electricity generation.”

Yep. Fossil fuels, maybe with the exception of natural gas (for now) are finally seeing real competition in two major areas of historic dominance: electricity generation and road transportation.

In electricity generation, renewables and battery systems now outcompete most new coal and gas fuel-powered plants economically. So if you want to generate electricity for the lowest price, the best choice increasingly is not something that burns fossil fuels.

It’s not altruism why we’re seeing renewable energy go up and to the right. It’s economics. They’re just cheaper.

And what’s worse for coal and gas is that they are aren’t done getting less expensive.

This article has stood the test of time pretty well from its publication in 2021 until now. Its predictions have come true (well, maybe less for wind, but certainly for solar).

It highlights why solar and batteries, in particular are so well poised to take on fossil fuels – the bigger they get, the cheaper they get:

"Unlike fossil fuels — which get more expensive as we pull more of them from the ground, because extracting a dwindling resource requires more and more work — renewable energy is based on technologies that get cheaper as we make more.

This creates a virtuous flywheel: Because solar panels, wind turbines, batteries and related technologies to produce clean energy keep getting cheaper, we keep using more of them; as we use more of them, manufacturing scale increases, cutting prices further still — and on and on."

We cover this more in our second article: “Why Climate Solutions Will Win,” but this phenomenon, known as Wright’s Law, states that every time the total demand for a manufactured good doubles, the costs of the end product go down by 20%, from economies of scale and newly discovered manufacturing efficiencies.

Fossil fuels aren’t a manufactured good. There’s not much more efficiency to be squeezed from them. And now they’re going up against renewables and batteries that are not only already generally cheaper, but are still just beginning their growth curves.

But what about oil? Not that much oil is used in electricity production (and the IEA’s prediction is about oil specifically after all). Which brings us to the second area fossil fuels are seeing their historic dominance under threat: road transportation.

In 2022, road transportation represented 47% of global oil demand

Meaning that almost half of oil demand globally is dependent on the continued use of a specific technology: Internal Combustion Engines (ICE) in cars and trucks. If you fill up your car with gas, you are driving an ICE vehicle. They have been synonymous with cars since the inception of the industry.

But the supremacy of ICE in road transportation is under threat. A new, superior technology has begun to reach escape velocity: electric vehicles (EVs).

The same kind of technology that powers your cordless drill will very likely power your car (if it doesn’t already).

Why are electric engines superior for the use case of driving?

Using an electric engine instead of an ICE one enables a car to do the same stuff, just better:

- Cheaper to Manufacture and Maintain: EVs tend to have 25 - 50 moving parts in their drive trains whereas ICE cars have 200 - 2,000. This unlocks both lower costs (it just costs less to manufacture and install 25 things than 2,000) and a lower likelihood of breaking down (moving parts = greater likelihood to break). Also no more oil changes!

- Cheaper to Fuel: According to CNET in 2025, EV drivers can expect to pay an average of $70.72 per month in electricity to “fuel up,” whereas the average IC car driver will pay $152 per month to drive the same distance.

- Faster: Electric cars don’t have gears, meaning they have much faster acceleration than ICE cars. For everyday drivers, this can make getting on the freeway more fun. But EVs also are setting new lap times at famous racetracks.

- Safer: EVs by: not carrying around combustible fuels, not needing a big engine in the front, and distributing batteries through the floor have proven to generally be safer than ICE vehicles. In 2023, 60x more ICE cars caught on fire (per 100k cars on the road) than EVs. And their lower center of gravity led to a lower injury rate per crash than ICE.

- More Convenient: If you own a home, you can fuel your car in your garage instead of at the pump.

- More Comfortable: EV engines make far less noise and vibration than an ICE engine, leading to a smoother driving experience. And because the engine and drive train can be distributed across the floor of the vehicle, they can be roomier than ICE cars (although this varies by model).

Now if you’re reading this in the US, you might be thinking to yourself, well, that’s all fine theoretically, but EVs certainly have their drawbacks. They tend to be more expensive to buy and they take a lot longer to charge and they have fewer places to charge than gas stations. This makes them more expensive and a lot more stressful for long distance driving.

You would indeed be correct in making such an observation in the US.

But remember. At some point, it too was more expensive to buy an ICE car than the preceding technology for getting around, a horse and buggy. It too was less convenient to drive an ICE car. There were more stables than gas stations. But that doesn’t take away from the fact that the technological potential for ICE cars was far higher than horses. At some point, those cost and convenience factors flipped as the superior technology surpassed adoption of the inferior one.

Now, we believe we are seeing the same trend happen, but this time to ICE engines and that future is arriving in China.

We’ll cover this in much more depth in the next chapter, but China today is living the electrified transportation future that the world could very well be seeing over the coming decade.

Chinese car manufacturers have applied their manufacturing prowess to EVs, enabling them to solve the problems still persistent for EVs in other countries today.

- Cost: In China, you can buy a pretty great electric car for just $14,000 USD that Motortrend reviewed “Pretty Darn Tempting”. Compare that $18k you have to pay for the lowest cost new car in the US that Car and Driver gives a 2.5/10.

- Charging Speed: BYD, the largest EV manufacturer in the world, has released 5-minute charging technology that is comparable to filling a gas tank.

- Charging Stations: China already has 20x more charging stations than in the US.

China has been able to do this, in part because, the other big advantage of electric cars is that they get to piggy-back off of decades of advances in electronics manufacturing. At the end of the day, an EV is just a giant piece of consumer electronic hardware, rather than a gas tank on wheels.

This is why a smartphone manufacturer like Xiaomi has been able to successfully enter and build significant market share in the Chinese auto-market in just a few years. They already had the in-house capabilities to make super advances electronics. This is just a bigger scale.

So, it should come as no surprise that in March, 2025 over half of Chinese car registrations were for electric cars.

And it should similarly come as no surprise that in 2024, China saw its first ever-decline in demand for petroleum (IEA).

If we are correct and that the Chinese auto market is a glimpse into what the global auto market will look like in 10 years, then oil is indeed facing an economic threat unlike they have ever seen before.

Half of oil today is used in road transportation. A superior technology to ICE engines has arrived and has already surpassed ICE-powered cars in one major global auto market. And, as a result, petroleum demand has already begun declining there.

If suffering rising production costs and thin margins wasn’t bad enough and facing the next generation of energy technology (renewables, batteries, and EVs) without a real answer wasn't bad enough…

What happens to fossil fuel demand when the country manufacturing most of the world’s solar panels, wind turbines, energy storage batteries, and EVs, decides it’s in its own best interest to geopolitically spread these superior technologies to the world?

Yep. Let’s talk more about China.

Chapter 5: China has a geopolitical incentive to replace oil demand with renewables + batteries

What do Russia, Saudi Arabia, and the United States all have in common?

They are major oil exporters.

Meaning they are all countries that other governments think twice about pissing off.

Why did the US not punish Saudi Arabia after it killed a US journalist? Oil.

Why did governments across Europe lose elections in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine? They lost access to cheap Russian gas and electricity prices spiked.

One way of dividing the geopolitical stage is between the energy haves and have nots. Those who have enough fossil fuels to export it to other countries and those who have to gratefully accept whatever fossil fuels they can get in order to keep their economies running.

Historically, to have access to domestic fossil fuel production has put a country and government in a position of strength on the world stage.

China has been on the other side of that divide. While they have large coal reserves, they do not have any meaningful oil deposits, leaving them with no choice but to import ever-greater amounts of oil.

So what does an aspirational country do when they can’t win the game? They change the rules.

Since the early 2010s the Chinese government has been systematically investing in ways to generate, store, and use energy without oil.

It’s working. For 2023, the IEA estimated that 96% of newly installed utility scale solar and wind cost less than new coal or natural gas plants, and 75% were cheaper than existing fossil fuel facilities.

The supply chain for new natural gas plants is getting bogged down, while solar is increasingly accessible.

We’re seeing more emerging markets with immature electricity grids like Pakistan opt for decentralized solar over traditional centralized power plants because of how cheap Chinese panels have become.

And that’s just solar, the most mature of the trifecta of solar, batteries, and EVs.

The Chinese EV market, after facing intense internal competition that has resulted in the best cars in the world, is now getting ready to export. Xpeng, a leading brand, is planning to double its global presence from 30 countries to 60 in 2025 alone.

And China is projected to represent over half of the energy storage batteries in the world by 2027.

Because while China does not have oil, it does have basically everything you need to make a ton of solar panels, and batteries, and great EVs. From the raw materials needed for each component, to the advanced manufacturing capabilities.

And they have an incentive to leverage those advantages on the world stage. The more solar panels they export, the more “Pakistans” we see that opt to skip the fossil fuel phase of development, opting for cheap renewables instead while increasing their dependence both sides of energy: the products needed to make energy (ie solar panels) and the products that use said energy (ie EVs).

The more China pushes solar, batteries, and EVs out into the world, the more energy demand we will see turn away from fossil fuels and towards these cheaper, better, faster, technologies. And the more of the world that embraces them, the more China is in a position to enjoy some of the geopolitical advantages that the major oil exporters do today.

So not only are oil’s profit margins already thin, but the largest manufacturing powerhouse in the world has a clear political incentive to replace oil demand with solar, battery, and EV demand. And barring an all out trade war with the world vs. China, there’s nothing really the fossil fuel lobby can do to stop them.

Which leads to the question: should we be correct that an oil demand plateau in the 2020s leads to a gentle decline in the 2030s and maybe a steep decline in the 2040s, what will that mean for the rest of the economy? In particular how will that impact industries that are dependent on oil?

Chapter 6: Contracting Oil Demand Could Have Major Downstream Effects

What leads one technology to replace another?

It generally doesn’t start out with the old technology being clearly better than the new onel. The first automobiles were much worse than a horse-drawn carriage. They were louder, more dangerous, prone to break, or even explode. Plus there was no place to park. They scared the horses. There weren’t any gas stations or repair shops. Stick with the horse, right?

So, how did cars possibly catch on? Their potential was much higher. They had the potential to do everything that a horse-drawn carriage did, but better: get people to further away destinations faster, at a fraction of the capital and operational cost.

When a new superior technology comes, it starts out worse and more expensive than the previous one. But enough people see the potential, it generates enough governmental support, and enough early adopters are excited to take the plunge, that it starts to catch on.

Each time, the new ascending technology followed a similar curve, known as the “S-Curve” of technology adoption.

It’s basically the process by which a new superior technology slowly, methodically eats the old technology’s lunch. As the new tech gets bigger, a virtuous cycle takes over where more demand generates more investment, which generates more governmental support (see China), which leads to more variety and better economies of scale.

We’ve covered a lot of the virtuous cycle half for renewables, batteries, and EVs in the above sections. So as the world focuses on the new, improved tech, what happens to the old one?

A death spiral begins. As more people switched to cars, demand for new carriages and buggies started to fall. Some factories began to go under and variety began to suffer. Hotels and inns saw the demand for stables on premises start to fall, so they let their stable hands go, making it harder to travel even if you still had a horse. Then the laggards who used their buggies as long as possible finally gave up after they couldn’t find anywhere to repair them or get new parts. And the takeover of the car was complete.

So what would a similar path look like for oil? If we are correct and we see fossil fuel demand plateau and begin declining as a superior technology (the trinity of solar, batteries, and EVs) outcompetes them economically, what will that industry contraction look like and which other industries could it impact?

Playing it out, the first industries to be impacted will be the oil drillers and any direct supporting companies (rig management, offshore support, etc.). As demand plateaus, we’d see a slowdown in the turnover of old oil wells to new ones. The expansionary, exploratory part of the industry would contract. We’d also likely see expenditures reduced on the next parts of the supply chain like refining and shipping to just replacing worn out equipment.

So, when demand stops growing, but isn’t (yet) shrinking, we’re probably still seeing any negative economic impacts contained in the fossil fuel industry itself (thus further hurting their share prices), but not necessarily a major downstream effect.

But that will change when the demand curve starts to angle from flat to down. This is where things could start to get ugly.

The problem with the fossil fuel industry is that because of the low margins, all of the machines and hardware had to get really big to make the economics work out. Oil rigs are big. Oil tankers are big. Oil refineries are big. Oil pipelines are big. They are all expensive to build and expensive to maintain.

Walmart’s big innovation was making up for low margins (deliberately low retail prices) with volume. Fossil fuel companies have done the same thing.

Such a strategy is all well and good in an expanding, ascending industry. Debt can be secured to build that new pipeline or construct that new refinery, because the financiers can be confident that there will be plenty of oil sloshing through to generate enough profits. But it can make for a very bumpy road for one in decline.

What happens when the pipeline doesn’t have enough throughput to justify staying in business? Or if they are still hanging on, but an extreme weather event (hello climate change!) causes a leak and major spill that is too expensive to clean up?

The options aren’t great in such a scenario. The financials don’t work to take on more debt. They’re not attractive for another buyer to take on.

Maybe something is worked out, but at some point, the math just stops adding up and the first big pipeline just goes under. And, because things in the fossil fuel industry are big, any big piece of the supply chain failing can have big domino effects.

Where will the refineries at the end of their pipeline get their oil? Is the only way to ship it over rail? It’s doable, but a lot more expensive, meaning now the refinery’s margins are squeezed further as they have to pay more for inputs as demand for their outputs fall.

At some point, the economic pressure is too great and the next link in the chain breaks and a major refinery goes under.

With the next domino having fallen, what happens to the industries dependent on those refineries? Can the cement manufacturer still operate profitably without their local fossil fuel supply chain? The steel mill? What about the airport? Or the shipping company?

The problem with fossil fuels is that they are big and heavy and need to be transported from wherever they can be found to wherever they can be useful (then they are lit on fire and you need more). This makes every fossil fuel supply chain fundamentally local to some extent. And each local supply chain is going to have a weakest link. As margins get squeezed, some inevitable event will cause that link to break. Some supply chains will be able to rebuild, just at higher costs (shipping refined oil on a tanker instead of a pipeline, etc.). Others may have major disruptions, especially if there is a sudden collapse.

What this will result is a series of sudden disconnects between supply and demand.

As demand gently curves down, supply will contract too. But only for so long until one of those links simply cannot survive with lower volume. Then snap. Supply suddenly drops below demand as a pipeline or refinery goes under. Leading the downward supply curve to probably look more like a downward stairway than a sloping line.

This will temporarily lead to a fossil fuel shortage and price hike, like the one we saw in 2022 after Russia invaded Ukraine. And such a price hike could lead to temporary boosts in profits for the industry and the continued investment in the remaining fossil fuel infrastructure.

But such price jumps are unlikely to be a saving grace for fossil fuels. Instead, they could accelerate its decline.

The higher oil prices rise, the more attractive their alternatives become. That is particularly true if businesses are also trying to account for further supply-side shocks from other links breaking in the fossil fuel supply chain.

And those temporary price jumps also could have an outsized impact on fossil fuel dependent industries, raising their costs, causing localized shortages, and similarly, giving further incentive for people and companies to look for alternatives.

This is why we not only exclude fossil fuels from our portfolios, but their high-carbon, dependent industries like cement, steel, shipping, and airlines. We believe they have outsized energy transition risk that is not being accurately priced into their valuations, that puts them at a long term disadvantage compared to alternatives that are not directly dependent on fossil fuels.

So, that’s our case against fossil fuels as a long term investment:

- They’ve generally been a drag on returns for the past 20 years.

- That’s because they are a high-volume, low-margin industry that has spent much of the past two decades actually losing money.

- Long term investors bet on innovation to either increase profits, capture more market share, or both. Fossil fuels don't have any more obvious innovations left to try as their last one, fracking, failed to deliver major profits.

- This lagging stock performance has all happened during a time of expanding fossil fuel demand. What will happen when demand falls if, say, a politically motivated China pushes its ever-cheaper solar panels, batteries, and EVs out to the rest of the world?

- And if fossil fuels really will be sunsetting, the decline won’t be smooth. Pieces of major infrastructure will stop being profitable, with their closures creating a negative cascade throughout a fragile supply chain, ultimately driving up costs and raising energy security concerns for fossil fuel dependent industries like heavy industry, airlines, and freight transportation. And its investors who will pay for the failure of such infrastructure.

But that’s just our take.

What do fossil fuel companies themselves project about their future growth?

The answer is surprising.

Chapter 7: Even oil companies are projecting modest demand growth (at best)

Given all of this, it’s of no surprise that even oil companies themselves are projecting flat to modest demand growth in the coming decades.

It’s one thing for the International Energy Agency (IEA) to call for peak oil. They do not have a financial stake on either side of the energy transition (although OPEC has given them a lot of flack for making that call).

It’s another thing for an oil company themselves to acknowledge that fossil fuel demand may plateau and even drop, and further belies the headwinds facing oil companies over the long term.

Let’s start with Shell. They released a report in 2025 labeled: “The 2025 Energy Security Scenarios.”

In it, they walk through three different scenarios the world could take in the coming decades.

- One with increased global trade and friendly competition on things like AI that drive up resource consumption but also accelerate clean energy (Surge).

- One where the world splinters into factional groups leading to a global slowdown in economic activity (Archipelagos).

- One where the world works to seriously reduce emissions.

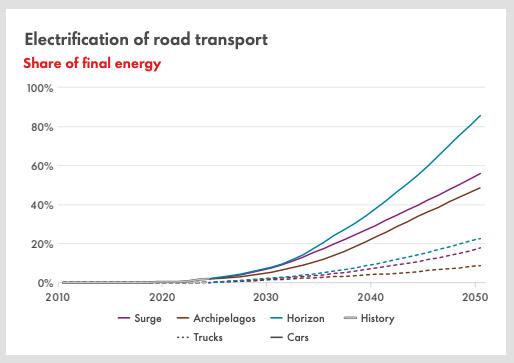

In all three scenarios, the role of fossil fuels in the global energy system steadily drops:

In all but one of them, the world is using less fossil fuels in 2060 than they are today.

And in each of them, it’s not the fossil fuel industry that is poised for tremendous growth in the coming decades, but their competition:

Given these projections, you would imagine that Shell would be rapidly investing in those “up and to the right” technologies while just maintaining its fossil fuel operations, right?

Nope.

Around the same time of this report, Shell also announced that they would be cutting their “low-carbon” CapEx expenditures to 10% of total CapEx (Capital Expenditures which are big pieces of infrastructure like a building or pipeline, a company pays for once). And it’s not like they were primarily investing in EVs or batteries. They were investing in hydrogen and carbon sequestration, two technologies that are still in their infancy that still may never pencil out at scale. Both would increase the cost of fossil fuels, further squeezing existing margins, so it’s not a surprise they would be cutting back.

This brings up the pervasive myth that fossil fuel companies are necessary capital partners in the energy transition. The data just doesn’t support that.

IEEFA estimates that only 1.4% of Global Clean Energy Investment came from fossil fuel companies in 2024.

It feels pretty clear that oil companies are going to be oil companies.

Their spending data supports this and their rhetoric certainly does as well as we write this in 2025. Even the most aggressively green of the oil majors, BP, who once referred to itself as “Beyond Petroleum” has doubled down on oil:

So what could we be getting wrong and oil companies getting right? Why are they doubling down in the face of their own slim profit margins and projections of plateauing demand?

The simple answer is that industries simply do not have an economic incentive to declare their own demise. It would raise their cost of capital (which we address in our bonds section) and therefore, actually hasten that very demise. A self-fulfilly prophecy.

But let’s dig into a more bullish outlook for the fossil fuel industry. Exxon’s 2050 projections aim to paint a rosier picture for oil’s longterm prospects.

They project that fossil fuels’ slice of the global energy mix will remain relatively stable over the coming 25 years (~55%), but that overall energy demand will be increasing rapidly. 55% of a bigger pie = more demand for oil.

Their claim rests on the belief that while developed nations will decrease their overall fossil fuel usage from things like renewables, EVs, and energy efficiency, developing countries will be rapidly expanding their populations in the coming decades with more of that population moving into the middle class.

So more people, with more income to buy more stuff = more energy demand = more oil.

To give them their due. Exxon is not crazy for putting out stats like this, it’s the same kind of projections about population the UN is making.

But we at Carbon Collective are pretty skeptical about such claims as they imply that developing countries will follow the exact same relationship between birthrates and industrial development as the US did. So, if a country reaches a similar level of “development” as the US had in the 1930’s then, it should have the same birthrate.

But technology is moving much faster. To just give an example, in the 1930’s oral contraceptives did not exist.

Empty Planet, a book from 2020, argues this point - that just assuming that developing countries will follow the same birthrate trends as the US or other developed countries is a far too simplistic approach. They argue that actually, we should be far more worried about flat or declining birthrates by 2050, rather than preparing for continued rising population.

The book came out in 2020, and so far, their predictions seem more correct to us.

In the 1950s the global birthrate per woman was 4.9 children. In 2023, it was 2.3.

A helpful number to remember in this kind of analysis is 2.1. That’s the population replacement rate, meaning if the world drops below 2.1 children per woman, we will actually see a decline of global population. At 2.3, we’re not that far off.

And this data is pretty enlightening.

Look at the developing/emerging market countries you expect to have quickly rising middle classes:

- India: 1.89

- China: 0.99

- Indonesia: 2.05

- Brazil: 1.58

- Vietnam: 1.86

These countries are still far behind the “development” trajectory of the US, but they already have lower birthrates than replacement today and are closing in on the 1.6 births per woman the US had in 2023.

In fact, the average birthrate for the 26 countries in MSCI’s Emerging Markets index in 2022 was just 1.85. Meaning we would expect to see populations across these fast growing economies shrink over the coming decades. Not rise.

For Exxon’s rising population + rising middle class math to be correct, we would need to see quickly growing middle classes in some of the poorest countries in the world, primarily in central Africa like the DRC, Niger, and Somalia.

While we very much hope all of these countries see meaningful economic growth in the coming decades (which could lift millions out of poverty), the populations are unfortunately a long way away from a global middle class lifestyle. The average daily income in these countries is something like $2 a day. A global middle class lifestyle income is ~$20/day. To go from $2 to $20 of income per day over the next 25 years would require sustained annual GDP growth of 9% per year. To put that kind of growth in perspective, that’s about how fast China grew from 1978 to 2023.

Could Niger, Somalia, and the DRC be the next China? It feels unlikely. China was able to sustain such historic growth due to their relative political stability following the Cultural Revolution. None of these countries are known for their strong political systems.

And even if they do take off and be the next China, who isn’t to say that these African countries wouldn’t pull a Pakistan and skip over fossil fuels right into distributed renewables, batteries, and EVs? Africa already did the same thing with a different technology, skipping land lines and going right to cell phones. Such a transition seems like the kind of thing China would be geopolitically interested in helping make happen...

So, we find specific arguments on why we will see sustained fossil fuel demand growth to be lacking. While they admit that fossil fuel usage per capita is likely to fall in developed countries from a combination of cheap renewables, batteries, and EVs, they claim this dip will be more than made up for by new demand coming from developing countries. But as outlined above, their rationale seems to rely on broad-brushstroke projections that don’t hold up well to scrutiny.

Instead, we believe the IEA set of assumptions for a late 2020’s plateau of fossil fuel demand, followed by an ongoing decline in the coming decades is the more likely scenario:

- Renewables, batteries, and EVs are a fundamentally superior technology to fossil fuels for many applications.

- Therefore, these technologies are scaling exponentially up the S-Curve of adoption, led by a geopolitically-incentivized China.

- 49% of fossil fuel demand is for road transportation. This is where we will probably see the greatest drops first.

- The fossil fuel industry has been operating as a high-volume, low-margin industry for decades now. While there are still small efficiencies to be gained from operational efficiency and greater scale, there is no technological “silver bullet” left to make it much cheaper to extract depleting fossil fuel resources.

- The massive scale of the fossil fuel industry will lead to an inevitably messy contraction process. The financially weakest links in the supply chain will break first, leading to shortages, price spikes, and general disruption for downstream industries reliant on a local supply.

- The volatility of this contraction will further push fossil fuel customers to renewables, batteries, and electrification to safeguard their own energy supply chains.

- Collectively, such actions will serve to only accelerate the downward death spiral of fossil fuels.

And that’s all without any climate-focused legislation or judicial rulings.

We (unfortunately) know climate change is going to get worse before it gets better. How will governments respond?

Chapter 8: The wildcard of governmental climate action

There’s one big X-factor we haven't yet covered in our analysis of why fossil fuels are a poor long-term action: climate change.

Fossil fuels make climate change worse.

People really don’t like climate change when they experience it.

People have (and very well may continue to) force governments to take action to address climate change by supporting fossil fuel alternatives, making fossil fuels more expensive, or even requiring fossil fuel companies to pay damages.

So how big of a difference could this make?

Well, let’s ask Shell.

In their “2025 Energy Security Scenarios report they detail a scenario, they dub “Horizon” in which the world puts policies in place to keep the world below 1.5ºC of warming by 2100.

Here is how they describe it:

“After 2030, Horizon brings society rapidly to net-zero emissions, and the scenario sets out the major interventions in the energy system required from policymakers to achieve that outcome. This includes the early retirement of some fossil-fuel assets, high carbon prices, the rapid introduction and scaling up of early-stage technologies and significant energy conservation through efficiency and even energy austerity. Governments are forced to limit societal choices, such as restricting the selling of internal combustion engine vehicles and dissuading excessive meat consumption.”

The result for fossil fuels? Look at the blue line below.

By 2050, fossil fuels will drop to just ~30% of primary energy usage in their Horizon scenario vs. 50-60% for the other two.

So policy can be a big, big lever over the coming decades. One that, at least according to Shell’s own projections, has the potential to cause fossil fuel’s share of the energy mix to drop 2x faster than it would have otherwise.

We call it the X-factor, because we don’t know how big of a lever it will be. Or anyone at all.

As just the 2020’s have demonstrated in the US, major climate policies like the Inflation Reduction Act can be put in place, only to see major pushback.

The fossil fuel lobby is still strong. But it's standing on increasingly shaky ground. Fossil fuel profit margins are low. Their costs are high (and rising as the “easy” deposits get exhausted). They are facing a competition unlike anything they have seen before in renewables, batteries, and EVs. And, unlike in the US, their lobbyists don’t have major political influence in China. If anything, China has a geopolitical imperative to supplant fossil fuels with their own energy sources: renewables, batteries, and EVs.

And then there’s climate change. As more people feel its impacts, how will they respond?

Remember, how the post-pandemic sudden rise in prices at the grocery store caused basically every open democracy in the world to kick out the current political party and elect the opposition into power?

Well, guess what is going to cause a lot of disruptions for farmers? Climate change.

And that’s just inflation. Add in extreme weather, wildfires, and rising sea levels… It’s not hard to see a world where there is far more consensus and urgency around climate change than there is today.

As we laid out in Chapters 1-6, we believe that regardless of how the world reacts to climate change, fossil fuels simply aren’t a smart long term investment. But should more meaningful legislative and/or judicial climate rulings come, the pain for fossil fuel companies, and their investors, could be significantly worse.

FAQ

Frequently asked questions

Could we be wrong?

Absolutely. Nobody knows what the future will unfold. Investing is the act of choosing which future you believe is most likely to happen.

We believe the most likely future is one where we see oil companies continue to decline in value as demand for their products drops. We believe this could be accelerated by climate-driven legislation that increases as the impacts of climate change are felt in more places around the world.

If you share our beliefs, then ClimateSmart could be a good fit for you. If not, then it's probably not the right fit.

Will renewables just meet new energy demand but not actually replace existing fossil fuel demand?

It's very possible. Some very smart analysts believe this is a likely scenario. They argue that humankind has rarely stopped using an energy source, but instead just start using a lot more of the new, better one.

We think this is not quite true. For example: humans really have stopped using literal "horsepower" in all but the least developed regions of the world. We are much more in the camp that humans are actually bad at spotting exponential technological transitions until after they have occurred.

But even if this scenario were to happen, we still think fossil fuels are not a smart long term investment. Long term investment returns are driven by growth. So, if this scenario does indeed prove true, would you rather be invested in the areas of energy that are actively growing or those that are stagnant?

But don't fossil fuel companies have high dividends?

Yes, they tend to, but if you back to Chapter 1, we're showing Total Return, which is inclusive of both capital growth and dividends.

As you can see, you would have generally been better off without fossil fuel companies (and their high dividends) in your portfolio over the last 20 years.

What if we never see any major anti-fossil fuel governmental action?

That would certainly be unfortunate for our global climate, but we believe that fossil fuels would be a poor long term investment even if climate change was not occurring.

Their profit margins are tight and will get worse as cheaper wells get exhausted. And they are now facing the most serious competition they ever have in renewables, batteries, and EVs. Three industries that all are cost competitive with the fossil fuel status quo and are rapidly innovating.

How can I get ClimateSmart in my company's retirement plan?

There's two ways. The easiest is to engage your HR leader to start a conversation with us about becoming your plan's 3(38) advisor. We serve well over 100 organizations and we stand behind how much better we make the 401(k) experience for everyone: leadership, HR, and participants.

But if your company already is working with an advisor they like, another good option is to explore simply adding our ClimateSmart Target Date Fund series to the plan.

Our difference

01.

We're clear eyed.

We think financial security and climate health are directly linked.

02.

We're independent.

We're not owned by a big bank or Wall Street firm.

03.

We're real people.

You'll feel it the moment you meet us.